|

|

Vol.

27 No. 2

March-April 2005

Responsible Care in Canada: The Evolution of an Ethic and a Commitment

by Jean M. Bélanger

To tell the story of Responsible Care and Sustainable Development in Canada is to tell the story of how an industry has evolved over a quarter century. The recurring theme in this story is trust—the key driver in the movement.

The initial concepts of Responsible Care in Canada grew out of a growing concern in the early 1980s that the chemical industry risked losing its public license to produce in Canada. In that period, pressures to regulate the chemical industry were building up and were particularly exacerbated by the major derailment of a hazardous-material train in late 1979 that resulted in the evacuation of Canada’s fifth largest city. The leaders of the chemical industry, through their membership on the Board of Directors of the Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association (CCPA), saw themselves at a difficult crossroad. The normal path forward would have led them to engage regulators in case-by-case discussions and challenges that, in the end, would have sapped totally the industry’s capabilities to develop its economic potential.

The Environmental Track

Those leaders, however, had the foresight to understand that the crux of the problem was much deeper. They understood, and this judgment was later confirmed in a major poll of public opinion, that the public’s concern was one of trust. The public, in fact, believed that the industry knew about the dangers associated with its products, but it did not tell anyone and even worse, it just did not care. A ranking of the chemical industry between the nuclear and tobacco industries became a real wake up call for the companies.

The industry leaders, therefore, deliberately chose to take the other path—one that would be anchored on gaining the trust of the public in communities near chemical plants and throughout Canada. Public trust, therefore, became the key driver. They quickly learned that trust could not be imposed and could not be gained by simply saying that they knew what to do and were doing it. Building trust required the application of three fundamental principles, which formed the cornerstones of Responsible Care:

- Doing the right thing—Up until then, the industry had, in large part, responded to the laws and regulations in existence, and worked to prevent new laws and regulations from being promulgated. Trust, however, required a commitment to do the right thing, whether or not laws and regulations existed in a specific area. In fact, visible performance in doing the right thing was an essential cornerstone before trust could hope to be achieved. This step radically changed the industry from simply focusing on regulatory compliance to being ethically oriented, which sometimes meant advocating for regulation if it was needed to implement improvement beyond the reach of member companies. Furthermore, any ethical basis had to have a societal component to it. The major difficulty was that, while an individual from a company might believe that he/she had strong values, issues had become extremely complex and involved a multiplicity of stakeholders. This complexity required companies to engage in meaningful dialogue with interested parties that incorporated the following principles:

— active listening to truly understand the underly- ing sources of concerns

— accurate presentation of the risks involved in operations and products, and efforts

being made to minimize them

— visible effort to integrate inputs from inter- ested parties into planning and implementation processes

— broad consensus that the benefits of the com- pany outweigh the risks

Placing Responsible Care within an ethical framework also represented a radical departure from what could have been a simple environmental management process, that is, another program just to be implemented. As an ethic, it required a radical change in the very nature or culture of companies, where the CEO had to obtain buy-in from all employees and had to take account of their environmental performance in an integrated and balanced manner with their economic

performance.

|

| Methanex, a Responsible Care company, operates this methanol and ammonia plant in Kitimat, British Columbia, Canada. |

- Caring about products from cradle to grave. Industry leaders quickly recognized that caring about products and their potential impact on people and the environment was not a divisible concept; it could not stop at the plant gate. While customers had to take on their own responsibilities in use and disposal, chemical companies’ ethics drove them to advise and assist those customers with proper handling. In fact, companies might even withhold products from customers who failed to handle them appropriately, thus practicing true product stewardship. Industry leaders also realized that the public would not understand differentiations about who had control of a product at any one time nor would the media encourage that understanding to take place.

- Being open and responsive to public concerns. Openness is the basis of accountability. In the end, the public had to determine, from its own observations, that an issue was being addressed because of a responsible management initiative and that the initiative was indeed addressing its own concerns. The public, however, was not the only beneficiary of openness. Companies, conscious that the weakest link could undermine everyone’s efforts at credibility, required confidence that all other companies were taking this as seriously as they were. This was further entrenched when a reputation survey found that a plant’s reputation was the same as the industry’s reputation once you reach 25 miles from the plant; as a result, individual positive reputations could be erased quite easily by another company’s actions. Finally, and perhaps most crucial, companies needed to satisfy themselves that they were not the weakest link in the system and that their efforts could stand up to external scrutiny. Because an individual company’s reputation was seen as dependant on that of its colleagues, CCPA was called upon to play a central role in bringing all the membership to the same level of commitment. The association accomplished this through the medium of Responsible Care Leadership Groups. All CEOs, or the most senior executive contacts in Canada, were brought together in six regional groups and asked to meet four times a year. Substitutions from that senior level were not generally allowed nor were other member company representatives included. At each meeting, led by CEOs, each company was expected to discuss its progress towards culture entrenchment and code completion, its successes, and its difficulties. Gradually, a spirit of trust and openness progressed to a point where CEOs/senior executive contacts felt able to challenge each other and accept concerns as well as offers of help.

The first public concerns about the chemical industry revolved around the environment and it became crucial for the industry to begin by examining its own behavior to ascertain that it was indeed doing the right thing. This started a voyage, an evolution, which took the chemical industry through publication of a Statement of Guiding Principles in 1983. Between 1985 and 1988 a set of codes was developed—accelerated by the Bhopal tragedy—that demonstrated industry’s commitment to environmental concerns from conception of products to their final disposal. Thus were laid the first two cornerstones of the trust foundation. The CEOs of the member companies then assured each other that they had indeed met their commitments through a signed statement to that effect.

There remained the third element of the trust foundation— accountability to the public. The first code developed by CCPA dealt with Community Awareness and Emergency Response. The industry intended to establish, right at the outset, credibility with its neighbors. Equally important was the establishment of a National Advisory Panel where all codes were scrutinized by a cross-section of public advocates prior to their adoption by the Board of Directors. These industry leaders knew what they were committing to, but it would have been meaningless if the commitment meant nothing to the public in which trust had to be achieved. This panel’s unedited report on the performance of the industry continues to this day. Parallel community advisory panels (CAPs) in each chemical plant location perform similar functions for each company and monitor the verification processes on an ongoing basis.

Even after the development of these cornerstones of Responsible Care, however, accountability was only a promise. The fact that CEOs stated they had met their commitment meant nothing to an untrusting public. In 1993, the process of public verification was initiated. Equally important was the voluntary establishment of an exhaustive report on all emissions that gave the means to track exactly the progress of each company and its promises for the next five years.

|

| Linking Resources to Consumer Goods, from A Kestone Sector Contributing to Our Standard of Living, published by CCPA. |

The Social Track

Since the Responsible Care initiative had to respond to public concerns, there was no doubt that the chemical industry first had to focus on meeting environmental, health, and safety (EH&S) issues. However, parallel to this effort, another international development was crystallizing public attention. In 1983, the United Nations appointed an international commission to examine the state of the environment globally, and to propose strategies for improvement. This commission, chaired by Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, culminated in the publication of the report Our Common Future, which focused attention on the interrelationships between the economy and the environment. However, the report further underlined how the social dimension was crucial in achieving this precarious balance.

One of the chemical industry leaders in Canada at the time was David Buzzelli, who had been appointed chairman, president, and CEO of Dow Chemical Canada, Inc. in 1986. He was a key thinker in the evolution of Responsible Care, committed to the concept of economic development, but without sacrificing environmental and social responsibilities. Following closely the issues raised by the Brundtland report and with his Responsible Care background, he became very active in the Canadian multistakeholder discussions that then took place on implanting the sustainable development culture within Canadian public policy processes. He participated in a task force that recommended Canada entrench the spirit of the Brundtland report in a permanent manner. The task force met in Winnipeg, Canada, and was unique in its composition. The members included environment ministers, labor leaders, business leaders, environment leaders, and representatives of native peoples. The task force recommended the formation of a National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE), which would be responsible for shaping Canada’s response to the Brundtland Commission recommendations.

Buzzelli was appointed as an initial member of the NRTEE. This is now an independent agency of the federal government in Canada, reporting directly to the prime minister, that provides advice on the economic-social-environmental interrelationships of issues and how to integrate them into public policy and implement them in the private sector. It consists of 25 senior multistakeholder representatives.

The social dimension has never been far from the surface of Responsible Care thinking. While environmental aspects could demonstrate a relatively causal relationship between the chemical industry and its impacts, the social dimension presented different challenges that had to be wrestled with, not only by the chemical industry, but also by almost all agents of economic society. In cooperation with a number of other Canadian industry associations, CCPA came to a conclusion that social responsibility had to be examined on two levels. First, a societal level where all stakeholders must reach consensus on their ever-evolving needs and the allocation of resources to each stakeholder in meeting them; this can include consideration of poverty, third-world development, human rights, and many others. Second, a sectoral or company perspective where industry must preserve and grow its natural and human capital.

How Much of Sustainable Development

Does Responsible Care Cover?

The figure below represents the scope of sustainable development as a globe, showing that there is a portion (not to scale) within the domain of industry. This area is divided into the 18 themes of sustainable development covered by CCPA’s Responsible Care initiative. The dotted line is intended to show the extent, ranging from zero at the “core” to 100% at the outer edge, to which Responsible Care might be seen to specifically address each theme. The shaded area represents the concept that much of sustainable development is beyond the role of the chemical industry. |

|

The second level represents a more direct causal relationship with the industry, but the demarcation boundaries are not as clearly defined as for environmental responsibilities. The chemical industry struggled—as did many other organizations in Canada—and is still struggling with the appropriate allocation of corporate social responsibility. In 1994, CCPA published A Primer on Responsible Care and Sustainable Development in which it tried to describe both the cohesion of the two concepts and equally, the uncertain areas where the scope of sustainable development clearly extended beyond Responsible Care. A review was carried out of principles of sustainable development integrated in a number of organizations, including the International Chamber of Commerce Business Charter for Sustainable Development, the National Round Table on the Environment, and the Economy Objectives for Sustainable Development, Agenda 21, of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. CCPA chose 18 sectoral themes common to many of these organizations and in its primer attempted to describe visually their relationship with Responsible Care. As can be seen in the figure to the right, there is a very high degree of congruence between the themes of sustainable development and those of Responsible Care. The pictorial description, however, provides recognition that certain social elements are truly societal in nature and beyond the scope of direct company actions.

As the public identified social concerns through the CAPs, these were integrated into each company’s responsibility portfolio. Community concerns have varied greatly from company to company, because of their operations, and so, social integration by individual companies has been experienced in very diverse manners. While Responsible Care had initially focused on EH&S concerns that were high on the collective agenda of the Canadian public and our industry, at the local plant level it was often the social issues that had to be addressed first. Many company examples can demonstrate this, all of which reflect the type of social context in which each company and company location operates.

|

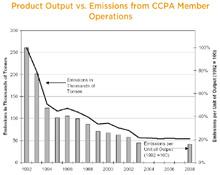

| Based on CCPA members’ total chemical production, emissions per unit of product are down as much as 83 percent since 1992. Source: Reducing Emissions—2003 Emissions Inventory and Five Year Projections published by CCPA. |

The chemical divisions of Nexen Inc. have been leaders in Responsible Care in Canada since its inception. More recently, segments of the petroleum operations of Nexen Inc., namely Balzac and the wholly owned subsidiary Canadian Nexen Petroleum Yemen (CNPY), became the first in Canada to become full Responsible Care Partners and, therefore, to submit to full compliance and verification. Operating in a totally different social context, CNPY has greatly expanded the vision of social responsibility normally perceived by other member companies and provides an excellent example of the need to respond to concerns as they are raised. CNPY along with the Masila Block Partners works cooperatively with the Ministry of Oil and the governor of Hadhramout to deliver community affairs programs in the area of its Yemen operations. It has focused these efforts in the areas of water, power, health, and education in a way that encourages capacity building within the communities. The sustainability of projects is viewed as a high priority. A number of examples clearly demonstrate this:

- CNPY’s field operations are very remote from the nearest medical facilities so the company provides free medical care to the communities in the vicinity of its operations. The average number of villagers that visit the clinic totals over 12 000 per year. Clinic medicine and consultation are provided free of charge to all users. In life threatening cases, local villagers are flown, by the CNPY contracted aircraft, to the hospital in Mukalla for further treatment. The company is also supporting improvements to the local medical capacity by helping to fund the construction of a new hospital in the coastal town of Ash Shihr through a grant to the Governor’s Office and the purchase of laboratory instruments for two other health centers.

- CNPY’s contribution covered the cost of several educational facilities. This funding, through the local authorities, ranges from maintenance of existing school buildings to building new basic education and secondary schools as well as supplying school furnishings for newly built schools. The company has also sponsored 20 post secondary Yemeni students to study at the University of Calgary and Southern Alberta Institute of Technology.

- CNPY has contributed financial support for a number of power plant and water supply projects as well. These include infrastructure projects to provide diesel-powered generators to remote villages as well as projects to extend the local power grid to small communities. The company has also brought fresh water to a number of small communities.

- CNPY has funded studies of fresh water resources in its area of operation and has drilled a number of water wells to support local communities. The operation of the wells and the water distribution networks is left to the local communities to manage. The company has also committed to a UN project to fund water and sanitation projects in the local community.

|

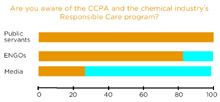

| Awareness of the Responsible Care program is very high among public servants and quite high among ENGOs. Conversely, media awareness of Responsible Care is quite low. Source: Responsible Care in Your Neighborhood, published by CCPA. |

The efforts to expand Responsible Care into the societal dimension continue to this day. In 2003, the CCPA approved a new statement of “The Responsible Care Ethic” which integrated formally this third dimension by stating:

“We are committed to do the right thing and be seen to do the right thing. We are guided towards environmental, societal, and economic sustainability by the following principles:

—We are stewards of our products and services during their life cycles in order to protect people and the environment.

—We are accountable to the public, who have the right to understand the risks and benefits of what we do and to have their input heard.

—We respect all people.

—We work together to improve continuously.

—We work for effective laws and standards, and will meet or exceed them in letter and spirit.

—We inspire others to commit themselves to the principles of Responsible Care.”

In addition, the sustainable development primer likely will be updated over the next year to include a section on social responsibility based on feedback received from the current public/peer Responsible Care verification process. Teams of activists, plant neighbors, and industry experts verify every company every three years. Between 2002 and 2005 they probed what companies were doing to meet their understanding of social responsibility expectations. Based on this, plus other stakeholder input, a code or guidance material on this aspect of Responsible Care may be developed.

|

Reflection on Drivers

The factors that have driven progress in Responsible Care are many and intricately woven. There can be little doubt that, at the outset, the initiative rested on the need to maintain the industry’s license to operate and the way to ensure this was to build trust, which, in some way became the initial proxy driver. Over time, however, as CEOs came to see the wisdom and intrinsic value of moving towards responsible behavior, trust became the main driver in its own right. The chosen route was to build trust and so, this aspect became the basic derived driver for the initiative.

Summary

Responsible Care is a dynamic statement of ethical concern, in a constant state of evolution. It was initiated in the early part of the 1980s as a simple one-page statement of principles touching the singular aspect of environmental responsibility. It has since evolved into a set of codes, verification processes, visible performance measurement and deeper understanding of the generality of the principles first stated. There has, however, been one constant, namely, that the whole exercise of Responsible Care is about building trust through ethical behavior, listening attentively to the evolving concerns of the public and providing responses that clearly demonstrate the concerns have been heard. In the same way, Sustainable Development has become the integration, in decision-making processes, of the economic-environmental-social concerns of that same societal public through mutual listening processes. The CCPA, by pursuing a dynamic and evolving Responsible Care approach is well aware of its ongoing commitment to meeting the sustainable development aspirations of Canadian society.

Jean M. Bélanger was president of the Canadian Chemical Producers' Association from 1979 to 1996. He is an Officer of the Order of Canada, Fellow of the Chemical Institute of Canada, and Fellow of the Engineering Institute of Canada. He is now partly retired but sits on the National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy. He was named to the UNEP Global 500 Roll of Honour in 1990.

www.ccpa.ca

Page

last modified 11 February 2005.

Copyright © 2003-2005 International Union of Pure and

Applied Chemistry.

Questions regarding the website, please contact [email protected]

|